Breaking

- MENU

Iran celebrated another year of victory of the ‘1979 Revolution’. However, the country-wide celebrations seem out of place after what Iran witnessed over the past year. Since the last anniversary, the Islamic Republic has had a tumultuous time marred by economic hardships, international isolation, and unprecedented protests that continue to engulf the country even after five months. The Iranian public awaits the eponymic ‘good times’ promised at the dawn of the Revolution. The idea of the Islamic government is under question as public belief in the regime peters out.

Compared to the past year, four broad observations can be made on where Iran stands on the 44th anniversary of the Islamic Republic. First, this was one of the most challenging years for the Iranian public, struggling with economic and social strife. Since 2020, Iranians have been anguished by Covid-19 mismanagement and worsening economic woes. Two-thirds of jobs lost during the pandemic are yet to be recovered. Meanwhile, the consistent inflation has broken the back of ordinary Iranians who are struggling to put food on the table. The World Bank reports suggest that economic performance is slowly improving. However, the benefits of an economic upturn are yet to trickle down to the masses.

Even the political landscape is mindful of such difficulties as the economic team of President Raisi faces severe censure by fellow conservatives. One of the three economy ministers had to quit after pressure from the Parliament. Moreover, President Raisi’s much-publicised ‘economic surgery’ (measures to improve economic performance) that notably removed subsidies on food items failed to deliver. This has all culminated in growing anguish among the masses, manifested in their continued violent protests against the regime.

Second, for the regime, too, the past year was the most challenging. The government failed to gauge the disenchantment among ordinary Iranians, even after two years of Covid-19 challenges that were fraught with maladministration. The changed laws for mandatory hijab backfired after the fateful death of Mahsa Amini, a 22-old Kurdish woman who died in the custody of Iran’s Morality Police. The ensuing protests spread like wildfire as Iranians throughout the country took part in violent protests involving recorded killings of security forces and burning state property.

Under the slogans of ‘Zan, Zindagi, Azadi’ (women, life, freedom), ‘death to the dictator’, and calls for an ‘end to the Islamic Regime’, the protests have posed the most significant internal security challenge to the regime since the Revolution. It became common during these protests to see burning the pictures of Ali Khamenei, Qassem Soleimani and even the founder of the Republic, Ayatollah Khomeini. Their statutes were defaced, and the once revered clerical establishment is now mocked as “turban tossing” (an extreme disrespect in the Shia culture) becomes frequent on the streets. Around 81 percent of Iranians (residing in Iran) do not support the Islamic Republic, according to a December 2022 study by GAMAAN (an independent foundation based in the Netherlands).

Intuitively, the regime resorted to violent crackdown and suppression by shutting down the internet and mass incarcerations, with instances of officials opening fire in public. It remains arguable how much the crackdown and arrests have helped the regime, but for the time being, it has reduced the intensity and scope of the protests. Yet, historically, such crackdowns act as nurseries for future anti-regime sentiments. The magnitude of the protests has been such that Khamenei and others like President Raisi have come to mellow their position on hijab by announcing amnesty and pardons to protestors.

Third, Iran seems to have found a new friend in the East. The complex realities of war in Ukraine have forced Moscow to look for partners, including Tehran. Iranian drones have been the centrepiece of this newfound bonhomie with Russia. Several delegations have been exchanged over the last year, with recent news of Russia providing Su-35 aircraft to Iran. The banks in the two countries are also devising bilateral arrangements to circumvent sanctions.

President Raisi has hailed this relationship with Russia as a foreign policy success. However, the reality of Iran-Russia relations is far from perfect. For instance, Russia allegedly spoiled the Vienna negotiations that were heading to some conclusion last year. Russia reportedly insisted on concessions in the nuclear deal against the possible US sanctions on Russia. Tehran first regarded this as a ‘rumour’ but then went on to damage control. Similarly, there have been back-and-forth statements by both sides on the success of the bilateral ties. Tehran appears to oversell, while Moscow seems to undersell the importance of the other side. As such, the relations are not a strategic milestone but a ‘marriage of convenience’.

Fourth, the never-ending JCPOA negotiations appear to be ending without any yields for Iran. The protests and crackdown have made the Biden administration and many European counterparts hesitant to engage Iran. The Raisi government insists that the administration’s policies are not accounting for the possible JCPOA revival. Yet, nobody in Iran’s hardliner leadership is willing to call off the negotiations, illustrating the expectations associated with the JCPOA. For such reasons, perhaps, the “window of opportunity” for the nuclear deal never seems to be closing.

As such, over the past year, the regime failed to deliver as it struggled to hold onto power while the public resentment of the regime and the Revolution has kept growing.

Note: This article was originally published in Financial Express on 17 February 2023 and has been reproduced with the permission of the author. Web Link

As part of its editorial policy, the MEI@ND standardizes spelling and date formats to make the text uniformly accessible and stylistically consistent. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views/positions of the MEI@ND. Editor, MEI@ND: P R Kumaraswamy

Prabhat Jawla has a Master’s degree in international relations from South Asian University, New Delhi. His areas of interest include geopolitics in West Asia with a particular focus on IRGC, Iran’s domestic and foreign policies and Indo-Iraq relations. He had worked as a research intern in West Asia Centre at Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA) and he tweets at @aprabhatjawla.

The maiden visit by Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, which aimed to strengthen the.....

Following the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini (also Zhina), widespread protests have gripped the Is.....

At the dawn of a new century in the Persian calendar, the Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khame.....

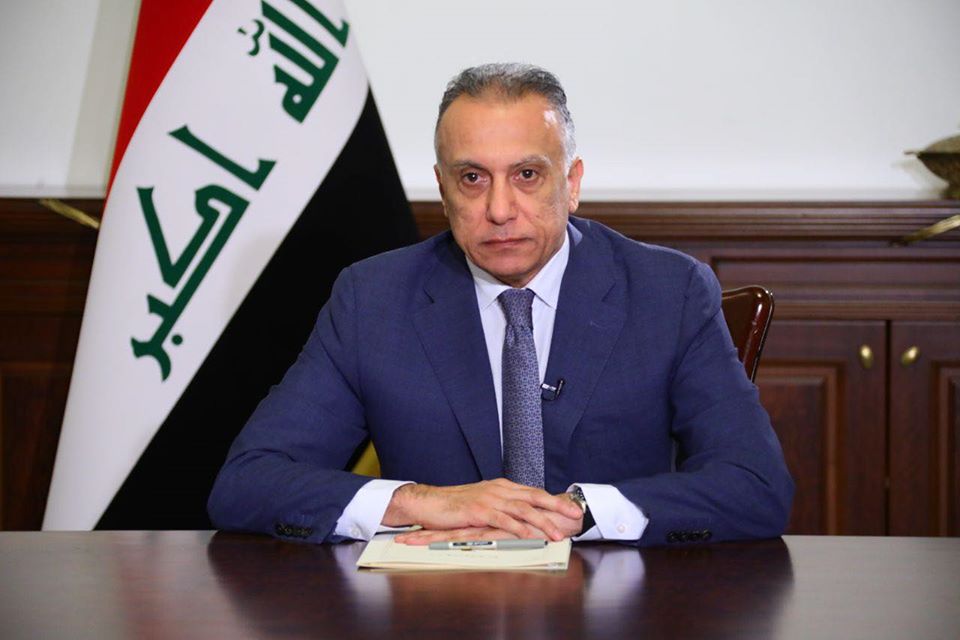

In May 2020, after months of political wrangling, the Iraqi Parliament (Council of Representatives) .....