Breaking

- MENU

Turkish state-run television appears to have not gotten the message: Turkey and the United Arab Emirates are burying the hatchet – one of several Turkish efforts to reduce tensions in the Middle East and prevent them from spinning out of control.

TRT 1 is set to broadcast a new and second season of Teskilat (The Organization), a series allegedly endorsed by Turkey’s intelligence agency, that portrays it as fighting a covert war against a thinly disguised Arab adversary, the United Arab Emirates.

The UAE-backed fictional organization is led by Zayed Fadi, a composite figure whose first name refers to Emirati Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, whom pro-government Turkish media long called the ‘prince of darkness.’ Fadi references controversial Abu Dhabi-based former Palestinian security chief Mohammed Dahlan, an associate of Prince Mohammed with close ties to the United States and Israel.

Known by his nickname Abu Fadi or Father of Fadi, Dahlan’s firstborn son, he often negotiates on behalf of the UAE in situations in which Prince Mohammed either prefers to maintain arm’s length or that further the former security chief’s Emirates-supported ambition to return to Palestine in a leadership role.

TRT released this week a trailer for the second season suggesting that it was moving ahead with the series but has yet to announce a broadcast date. Whether it does will say much about the solidity of the Turkish and Emirati efforts to contain their differences by focusing on economic issues.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan emphasized economics after talking by phone this week for the first time in eight years to Prince Mohammed and meeting earlier with the crown prince’s brother and national security advisor Tahnoun bin Zayed Al Nahyan when he last month visited Ankara.

The state-controlled Emirates News Agency (WAM) reported that the advisor’s visit was meant to “strengthen bilateral relations, especially economic and trade cooperation and investment opportunities in the fields of transportation, health, and energy.”

TRT’s decision on whether to broadcast Teskilat’s second season is likely to serve as a bellwether for the fragility of other efforts to contain the Middle East’s deep-seated disputes, including those between the UAE and Qatar as well as Saudi Arabia on the one hand and Turkey and Iran on the other.

The apparent Turkish-UAE approach of focusing on trade and investment while freezing geopolitical differences is a formula that has yet to prove workable in the Middle East, particularly given that regional disputes are often inter-connected.

Syria is one such flashpoint among many. The UAE has led efforts to restore the legitimacy of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime by engineering its return to the Arab fold. The League of Arab States suspended Syria eight months into the country’s brutal civil war on Turkey’s doorstep. Turkish troops in northern Syria, dispatched to ensure that no Kurdish entity emerges on the Syrian side of the border, have repeatedly clashed with Al-Assad’s military.

To succeed, the UAE, which reopened its embassy in Damascus in 2018, needs the backing of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia has suggested that it in principle backs the UAE effort by sending its intelligence chief, Gen Khalid Humaidan, to Damascus in May to discuss a reopening of the Saudi embassy in the Syrian capital.

The problem is that Saudi Arabia is seeking to leverage its backing in its stalled Iraqi-mediated talks with Iran. Iran is, together with Russia, Al-Assad’s main backer. Iran has so far rejected a Saudi suggestion that it would re-establish relations with Syria in exchange for Iran pressuring Houthi rebels in Yemen to genuinely negotiate an end to the 6.5 year-long war that has ravaged the country.

The Eastern Mediterranean is another flashpoint in which Emirati geopolitics combine with economics to compete with Turkish ambitions. Israel finalized this week the sale to the UAE of a 22 per cent stake in its Tamar offshore natural gas field for US$1.1 billion.

A member of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum, which groups Israel, Egypt, Israel, Greece, Cyprus, Italy, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority but not Lebanon and Syria that have claims of their own, the UAE hopes to export oil to Europe through an Israeli pipeline that would link it to the ports of Eilat on the Red Sea and Ashkelon on the Mediterranean.

For its part, Turkey has signed an agreement with Libya that carves up the eastern Mediterranean into exclusive economic zones for each country. The zones overlap with claims by members of the Forum as well as Lebanon and Syria.

In the world of Teskilat’s conspiracy-driven plot, Syria is one battlefield in which a secretive and mysterious unit of Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization (MIT) battles Fadi’s Organization. Fadi’s Organization struggles in Syria to escape the superiority of Turkish drones, has aligned itself with the Islamic State and the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK) to strike at targets in Turkey, and cooperates in Europe with the far-right and neo-Nazis to attack Turks in Europe.

The series builds on allegations by members of Erdogan’s government and ruling party that the UAE had funded a failed 2016 military coup. Turkey has issued an arrest warrant for Dahlan for his alleged role in the coup and has offered a reward of US$1.2 million for information that leads to his arrest.

The UAE at the time, despite already strained relations with Turkey, persuaded the six-nation Gulf Cooperation (GCC) that also includes Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait Bahrain and Oman to designate the movement of Fethullah Gulen as a terrorist organization. At the same time, the UAE expelled two Turkish generals accused of having been part of the coup. Turkey has said the Gulen movement was behind the attempted military takeover.

Broadcasting Teskilat’s second season would likely be seen by the UAE as particularly provocative after authorities in Dubai, in a goodwill gesture, briefly detained Sedat Peker, an alleged mobster with links to the Turkish deep state, to demand that he stop posting online videos accusing senior government officials and businessmen of corruption. The videos went viral and were long the talk of the town in Ankara and Istanbul.

Home to businessmen and deposed leaders who have escaped corruption charges, the UAE has so far refused to respond to a Turkish request to extradite Peker. Given the UAE’s willingness to grant refuge to the fallen high and mighty with no questions asked about the source of their wealth they had already parked in the country or brought with them, it may be easier for Turkey to cancel Fadi than for the UAE to return Peker.

The UAE’s latest refugee, ousted Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, has denied allegations that he fled his country with US$169 million in cash. The replacement of Ghani by the Taliban coupled with the role of Qatar as a major diplomatic and logistics go-between in the aftermath of the US withdrawal from Afghanistan and the role Turkey plays, together with Qatar, in getting Kabul’s airport operational again may be one reason that the UAE is seeking to accelerate its rapprochement with Ankara.

Doing away with Fadi is low hanging fruit for Turkey even though Teskilat’s popularity may spark something of a domestic backlash on social media. It would, however, not remove the major geopolitical and ideological differences with the UAE that inevitably will colour efforts to focus on trade and investment.

The current effort to improve relations contrasts with failed past attempts when Turkish rejected Emirati offers of investment in exchange for the expulsion of members of the Muslim Brotherhood and changes in Turkish regional policies.

The UAE likely takes heart from Turkey’s recent crackdown at Egypt’s request on Egyptian opposition television broadcasters in Istanbul to further a rapprochement between Ankara and Cairo as well as Erdogan’s indication last week that he would welcome Emirati investments.

Turkish journalist and analyst Fehim Tastekin asserted however that plans for cooperation with Iraq presented by Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cauvusoglu at a recent regional summit in Baghdad signalled “Ankara’s intent to maintain its interventionist posture.”

Cavusoglu proposed a motorway and railroad that would link northern Syria to Bagdad in ways that would circumvent Kurdish dominated areas of northern Iraq, complicate the movement of Iraqi and Syrian Kurdish fighters, and facilitate Turkish access to the city of Mosul.

“The problem is always the discrepancy between what Turkey promises and what Turkey does. Erdogan will have to prove this time that things are different. That could prove to be a tough proposition,” said an Arab diplomat.

Note: This article was originally published in the blog, The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer and has been reproduced under arrangement. Web Link

As part of its editorial policy, the MEI@ND standardizes spelling and date formats to make the text uniformly accessible and stylistically consistent. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views/positions of the MEI@ND. Editor, MEI@ND: P R Kumaraswamy

James M. Dorsey is a Senior Fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies as Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, co-director of the Institute of Fan Culture of the University of Würzburg, and the author of the blog, The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer. Email: jmdorsey@questfze.com

The final run-up to the 2022 World Cup and the tournament's management is make-it-or-break-it ti.....

Former Qatari emir Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, the father of the Gulf state's current ruler, Tam.....

The Biden administration is mulling whether to grant Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman sovereig.....

Qatar's 2022 World Cup promises to benefit not only itself but also to provide an unintended eco.....

A potential revival of the Iran nuclear accord is likely to test the sustainability of Middle Easter.....

With the fate hanging in the balance of the 2015 international agreement that curbed Iran’s nu.....

At first glance, there is little that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, an Islamist and nation.....

Europe is likely to shoulder the brunt of the fallout of a rapidly escalating crisis over Ukraine. M.....

An Israeli NGO gives the United Arab Emirates high marks for mandating schoolbooks that teach tolera.....

How sustainable is Middle Eastern détente? That is the $64,000 question. The answer is probab.....

Qatar has begun to cleanse its schoolbooks of supremacist, racist or derogatory references as well a.....

Long banned, Christmas has finally, at least tacitly, arrived in Saudi Arabia; just don’t use .....

Increasingly, compliance with US sanctions against Iran could emerge as a litmus test of the United .....

Footballers with diametrically opposed views on homosexuality and alcohol consumption have sparked h.....

Saudi Islamic affairs minister Abdullatif bin Abdulaziz al-Sheikh has ordered imams in the kingdom t.....

The United States has signalled in advance of next week’s Summit for Democracy that it is unli.....

A cursory look at Saudi Arabia and Iran suggests that emphasizing human rights in US foreign policy .....

When seven-time Formula One world champion Lewis Hamilton wore a helmet this weekend featuring the c.....

It has been a good week for United Arab Emirates Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed. Headline-grabbing,.....

Just in case there were any doubts, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu demonstrated with his .....

Sudan is the exception to the rule in the United Arab Emirates’ counterrevolutionary playbook......

Former Saudi intelligence chief Prince Turki AlFaisal Al Saud must have gotten his tenses mixed up w.....

An Indonesian promise to work with the United Arab Emirates to promote ‘moderate’ Islam .....

As Middle Eastern states attempt to manage their political and security differences, Muslim-majority.....

The future of US engagement in the Middle East hangs in the balance. Two decades of forever war in A.....

It may not have been planned or coordinated but efforts by Middle Eastern states to dial down tensio.....

Gulf States are in a pickle. They fear that the emerging parameters of a reconfigured US commitment .....

Two separate developments involving improved relations between Sunni and Shiite Muslims and women&rs.....

On their way from Tel Aviv airport to Jerusalem in 1977 then Israeli Deputy Prime Minister Yigael Ya.....

Saudi and Emirati efforts to define ‘moderate’ Islam as socially more liberal while bein.....

The Taliban takeover of Afghanistan perpetuates a paradigm of failed governance in the Muslim world .....

Israel’s first post-Netanyahu government is seeking to rebuild fractured relations with the Je.....

Taliban advances in Afghanistan shift the Central Asian playing field on which China, India and the .....

Boasting an almost 1,000-kilometre border with Iran and a history of troubled relations between the .....

This month’s indictment of a billionaire, one-time advisor and close associate of former US Pr.....

A recent analysis of Middle Eastern states’ interventionist policies suggests that misguided b.....

The United States and Iran seem to be hardening their positions in advance of a resumption of negoti.....

A recent unprecedented alliance between Muslims and Evangelicals takes on added significance in a wo.....

China may have no short-term interest in contributing to guaranteeing security in parts of a swath o.....

The rise of hard-line President-elect Ebrahim Raisi has prompted some analysts to counterintuitively.....

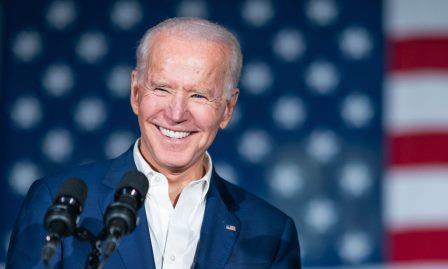

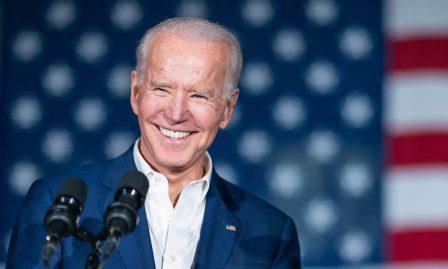

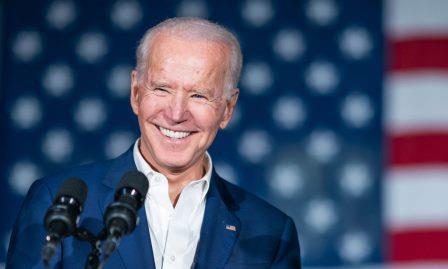

US President Joe Biden may have little appetite for Israeli-Palestinian peace making but seems deter.....

Recent announcements by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of plans to turn the kingdom into a transpo.....

Saudi Arabia has stepped up efforts to outflank the United Arab Emirates and Qatar as the Gulf&rsquo.....

Eager to enhance its negotiating leverage with the United States and Europe, Iran is projecting immi.....

Former Crown Prince Hamzah bin Hussein has papered over a rare public dispute in the ruling Jordania.....

Former Crown Prince Hamzah bin Hussein has papered over a rare public dispute in the ruling Jordania.....

In a sign of the times, Turkish schoolbooks have replaced Saudi texts as the bull’s eye of cri.....

Saudi Sheikh Salman al-Awdah, a popular but controversial religious scholar who has been mostly in s.....

Recent clashes in the Iranian province of Sistan and Balochistan highlight Iran’s vulnerabilit.....

Two decades of snail pace revisions of Saudi schoolbooks aimed at removing supremacist references to.....

A little acknowledged provision of the 2015 international agreement that curbed Iran’s nuclear.....

Religion scholar Esra Ozyurek has a knack for identifying trends that ring warning bells about where.....

A projected sharp reduction in trade between the United States and China in the next two years coupl.....

Public debates about China’s Middle East policy are as much internal Chinese discussions as th.....

Saudi Arabia has taken multiple steps to polish its tarnished image in advance of this weekend&rsquo.....

An Emirati offer to invest in Israel’s most controversial soccer club could serve as a figurat.....

A close read of the agreement between the United Arab Emirates and Israel suggests that the Jewish s.....

A rift between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia throws into sharp relief deepening fissures in the Muslim w.....

Rare polling of public opinion in Saudi Arabia suggests that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman may be.....

China is contemplating greater political engagement in the Middle East in what would constitute a br.....

Europe is progressively being sucked into the Middle East and North Africa’s myriad conflicts......

China looms large as a potentially key player alongside Russia and Iran in President Bashas al-Assad.....

Civilizationalist leaders, who seek religious legitimacy, cater to a religious support base or initi.....

A decision by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and non-OPEC producers like R.....

The Coronavirus pandemic points a finger not only at the colossal global collapse of responsible pub.....

Syria’s announcement of its first COVID-19 case highlights the public health threat posed by w.....

The fight in this week’s Democratic primaries may have been about who confronts Donald J. Trum.....

A podcast version of this story is available on Sound cloud, ITunes, Spotify, Stitcher, Tune In, Spe.....

Saudi Arabia may have been getting more than it bargained for when authorities in Khujand, Tajikista.....

At the core of US president Donald J. Trump’s maximum pressure campaign against Iran lies the .....

The Iranian port city of Bandar-e-Mahshahr has emerged as the scene of some of the worst violence in.....

Saudi efforts to negotiate an end to the Yemen war in a bid to open a dialogue with Iran could call .....

China is manoeuvring to avoid being sucked into the Middle East’s numerous disputes amid mount.....

Fears of a potential military conflict with Iran may have opened the door to a Saudi-Iranian dialogu.....

By the law of unintended consequences, US President Donald J. Trump’s mix of uncritical and cy.....

Little suggests that fabulously wealthy Gulf States and their Middle Eastern and North African benef.....

A controversial former security official and Abu Dhabi-based political operator, Mohammed Dahlan, ha.....

Russia, backed by China, hoping to exploit mounting doubts in the Gulf about the reliability of the .....

China and Russia are as much allies as they are rivals. A joint Tajik-Chinese military exercise in a.....

Thought that sectarianism was a pillar of the Saud Iranian rivalry? Think again, think Kashmir where.....

These are tough times for Saudi Arabia. The drama enveloping the killing of journalist Jamal Khas.....

Saudi plans to become a major gas exporter within a decade raise questions about what the .....

A Turkish-Chinese spat as a result of Turkish criticism of China’s crackdown on Turkic Mu.....

This week’s suicide attack on Revolutionary Guards in Iran’s south-eastern province of S.....

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s three-nation tour of Asia is as much about demonstrat.....

It may be reading tea leaves but analysis of the walk-up to Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman&r.....

Alarm bells went off last September in Washington's corridors of power when John Bolton&rsq.....

US President Donald J. Trump’s threat to devastate Turkey’s economy if Turkish troo.....

Pakistan is traversing minefields as it concludes agreements on investment, balance of payments supp.....

A heavy soup made of pulled noodles, meat, and vegetables symbolizes Central Asia’s close cult.....

As far as Gulf leaders are concerned, President Donald J. Trump demonstrated with his announced.....

When President Recep Tayyip Erdogan recently declared that Turkey was “the only country that c.....

A draft US Senate resolution describing Saudi policy in the Middle East as a "wrecking ball&quo.....

As Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman tours friendly Arab nations in advance of the Group of 20 .....

When Saudi General Khalid bin Sultan bin Abdul Aziz went shopping in the late 1980s for Chinese medi.....

Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan lands in Beijing on November 3, the latest head of government to.....

Saudi Arabia and Turkey, despite being on opposite sides of Middle Eastern divides, are cooperating .....

It’s easy to dismiss Iranian denunciations of the United States and its Middle Eastern allies .....

An attack on a military parade in the southern Iranian city of Ahwaz is likely to prompt Iranian ret.....

A Financial Action Task Force (FATF) report criticizing Saudi Arabia’s anti-money laundering a.....

Desperate for funding to fend off a financial crisis fuelled in part by mounting debt to China, Paki.....

Iran has raised the spectre of a US-Saudi effort to destabilize the country by exploiting .....

A possible ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, the Islamist group that controls the Gaza S.....

With multiple Middle Eastern disputes threatening to spill out of control, United Arab Emirates mini.....

Embattled former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak was the main loser in last month&rsq.....

Lurking in the background of a Saudi-Moroccan spat over World Cup hosting rights and the Gulf crisis.....

Amid ever closer cooperation with Saudi Arabia, Israel’s military appears to be adopting the k.....

Mounting anger and discontent is simmering across the Arab world much like it did in the w.....

Argentina’s cancellation of a friendly against Israel because of Israeli attempts to exploit t.....

Conventional wisdom has it that China stands to benefit from the US withdrawal from the 2015 interna.....

Saudi Arabia’s bitter rivalry with Iran has spilled onto Asian soccer pitches with t.....

A controversy in Algeria over the growing popularity of Saudi-inspired Salafi scholars spotlights th.....

Subtle shifts in Chinese energy imports suggest that China may be able to exert influence in the Mid.....

Egyptian general-turned-president Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi won a second term virtually unchallenged in w.....

Protests have erupted in Iran’s oil-rich province of Khuzestan barely three months after the I.....

Debilitating hostility between Saudi Arabia and Iran is about lots of things, not least who will hav.....

Saudi Arabia, in an indication that it is serious about shaving off the sharp edges of its Sunni Mus.....

The Middle East has a knack for sucking external powers into its conflicts. China’s ventures i.....

A Saudi draft law could constitute a first indication that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s .....

Turkish allegations of Saudi, Emirati and Egyptian support for the outlawed Kurdish Workers Party (P.....

Prominent US constitutional lawyer and scholar Alan M. Dershowitz raised eyebrows when he described .....

Plans to open a Salafi missionary centre in the Yemeni province of Al Mahrah on the border with Oman.....

If week-long anti-government protests in Iran exposed the Islamic republic’s deep-se.....

Kuwaiti billionaire Maan al-Sanea should have seen it coming after Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin S.....

Long-standing Saudi efforts to dominate the pan-Arab media landscape appear to have moved into high .....